Queued Events

In this article I am discussing Queued Events. Queued Events are a Windows kernel synchronization mechanism that I invented for WinFsp - FUSE for Windows. Queued Events behave like kernel Synchronization Events (i.e. Win32 auto-reset events), but provide scheduling characteristics similar to those of I/O Completion Ports.

The Problem

During the later stages of WinFsp development I decided to do some performance testing to understand its behavior and find opportunities for optimization. I found out that WinFsp performed very well in most tested scenarios, but there was one test that seemed to have bad performance for no particular reason.

I ended up profiling this issue using xperf (included in the Windows Performance Toolkit), which allows for kernel-level profiling. I spent considerable time looking at the profiling results, but could identify no obvious issue with my code.

After a day or two of doing this and being stumped I finally had a lightbulb moment: what if the issue is not with my code, but with how the OS schedules threads? Sure enough I had xperf trace context switches and found that on good runs the OS would context switch my file system threads relatively rarely; on bad runs the OS would context switch my threads excessively.

After contemplating this issue I realized that this was happening because the OS was trying to schedule my threads in a "fair" manner. Windows in general tries to give every thread a chance to run. This can be counter-productive in server-like programs (such as file systems), where all server threads are equivalent and it is actually better to reuse the same thread (if possible) to avoid context switching and other negative effects.

The Solution

One way of looking at WinFsp is as an IPC (Inter-Process Communication) mechanism. The Windows kernel packages file system operations (open, close, read, write) as IRP’s (I/O Request Packets) which it sends to WinFsp. WinFsp places them in an I/O Queue; at a later time the threads in a user mode file system retrieve the IRP’s from the I/O Queue and service them.

The I/O Queue had gone through multiple iterations, but at the time I was looking at this issue it was using Windows kernel Synchronization Event’s (Win32 auto-reset events) for managing threads. The problem was that a wait on a Synchronization Event would be satisfied in a "fair" manner, thus resulting to excessive context switching and bad performance in some circumstances. I needed to find a way to convince Windows to schedule my threads in an "unfair" manner, giving preference to the same thread as much as possible.

I started considering different schemes where I would associate a different event per thread thus being able to wake up the "correct" thread myself and effectively writing my own mini-scheduler. Luckily I had another lightbulb moment: I/O completion ports already do this better than I would ever be able to!

The kernel portion of an I/O Completion Port is called a KQUEUE. KQUEUE’s are (unfortunately) not directly exposed to user mode, however they are at the core of the user mode I/O Completion Ports. KQUEUE’s are the main reason I/O Completion Ports are so fast as they provide the following scheduling characteristics:

-

They have a Last-In First-Out (LIFO) wait discipline.

-

They limit the number of threads that can be satisfied concurrently.

I briefly considered the idea of building I/O Queues directly on top of KQUEUE’s, but soon dismissed this idea because I/O Queues are not simple queues but provide additional services, such as IRP cancelation, IRP expiration, etc.

Queued Events

In an ideal scenario I wanted to continue using my implementation of I/O Queues which had undergone considerable testing and I knew it worked. But somehow I had to convince the Windows kernel to change the scheduling characteristics of Synchronization Events to mirror those of a KQUEUE.

Then I had lightbulb no 3: Queued Events or how to make a queue behave like a Synchronization Event.

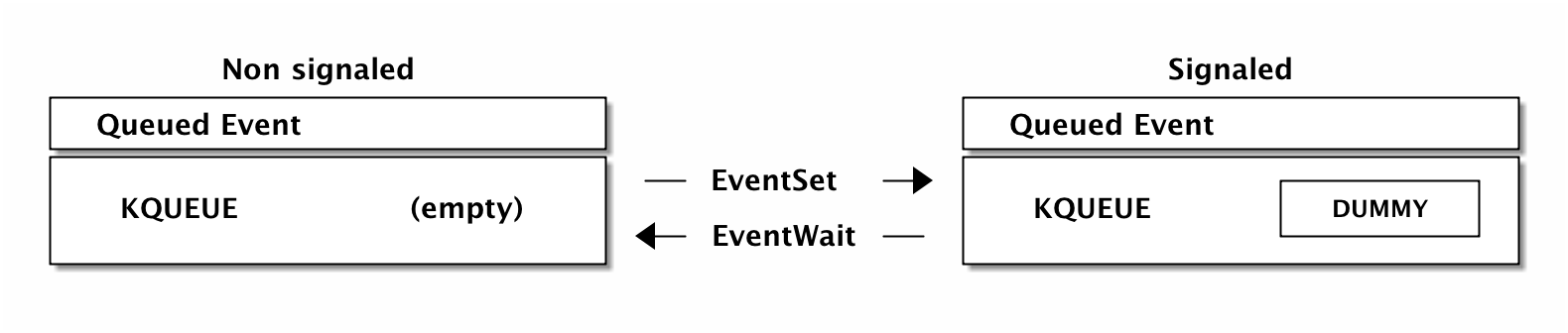

Here is how Queued Events work. A Queued Event consists of a KQUEUE and a spin lock. There is also a single dummy item that can be placed in the KQUEUE.

The KQUEUE is guaranteed to contain either 0 or 1 items. When the KQUEUE contains 0 items the Queued Event is considered non-signaled. When the KQUEUE contains 1 items the Queued Event is considered signaled.

To transition from the non-signaled to the signaled state, we acquire the spin lock and then insert the dummy item in the KQUEUE using KeInsertQueue. To transition from the signaled to the non-signaled state, we simply (wait and) remove the dummy item from the KQUEUE using KeRemoveQueue (without the use of the spin lock).

EventSet:

AcquireSpinLock

if (0 == KeReadState()) // if KQUEUE is empty

KeInsertQueue(DUMMY);

ReleaseSpinLock

EventWait:

KeRemoveQueue(); // (wait and) remove item

First notice that EventSet is serialized by the use of the spin lock. This guarantees that the dummy item can be only inserted ONCE in the KQUEUE and that the only possible signaled state transitions for EventSet are 0→1 and 1→1. This is how KeSetEvent works for a Synchronization Event.

Second notice that EventWait is not protected by the spin lock, which means that it can happen at any time including concurrently with EventSet or another EventWait. Notice also that for EventWait the only possible transitions are 1→0 or 0→0 (0→block→0). This is how KeWaitForSingleObject works for a Synchronization Event.

We now have to consider what happens when we have one EventSet concurrently with one or more EventWait’s:

-

The EventWait(s) happen before KeReadState. If the KQUEUE has an item one EventWait gets satisfied, otherwise it blocks. In this case KeReadState will read the KQUEUE’s state as 0 and KeInsertQueue will insert the dummy item, which will unblock the EventWait.

-

The EventWait(s) happen after KeReadState, but before KeInsertQueue. If the dummy item was already in the KQUEUE the KeReadState test will fail and KeInsertQueue will not be executed, but EventWait will be satisfied immediately. If the dummy item was not in the KQUEUE the KeReadState will succeed and EventWait will momentarily block until KeInsertQueue releases it.

-

The EventWait(s) happen after KeInsertQueue. In this case the dummy item in is the KQUEUE already and one EventWait will be satisfied immediately.

|

Note

|

Queued Events cannot cleanly support an EventClear operation. The obvious choice of using KeRemoveQueue with a 0 timeout is insufficient because it would associate the current thread with the KQUEUE and that is not desirable. KeRundownQueue cannot be used either because it disassociates all threads from the KQUEUE. |

The complete implementation of Queued Events within WinFsp can be found here: https://github.com/winfsp/winfsp/blob/v1.1/src/sys/driver.h#L655-L795

Queued Events Scheduling Characteristics

Queued Events encapsulate KQUEUE’s and therefore inherit their scheduling characteristics:

-

They have a Last-In First-Out (LIFO) wait discipline.

-

They limit the number of threads that can be satisfied concurrently.

These characteristics are desirable because they reduce the number of context switches thus speeding up the WinFsp IPC implementation. Performance testing immediately after the incorporation of Queued Events into WinFsp showed significant performance improvements; profiling with xperf showed that context switches among file system threads were now a relatively rare event!